When the Boxing Writers Association of American holds its annual awards dinner in New York on 30 April, it will mark the organization’s 100th dinner and the start of its 100th year of existence.

The Boxing Writers Association of Greater New York (as the BWAA was originally known) was founded by Damon Runyan, Paul Gallico, Ed Sullivan, Nat Fleischer, Edward J Neil and Wilbur Wood with the stated mission of improving conditions at boxing events for New York writers and their visiting colleagues.

Babe Ruth headed the list of celebrities who attended the organization’s first dinner which was held at the Hotel Astor on 25 April 1926. Five of boxing’s eight world champions were there, as were writers from 20 cities. The New York Times trumpeted the keynote address given by New York City mayor James J Walker with the headline, “Keep Boxing Clean, is Mayor’s Warning.” Beneath that, a sub-headline declared, “Walker Tells 1,000 at Writer’s Dinner, Police Will Aid in Driving Out Undesirables.”

“The Mayor,” the article recounted, “said the day of the thug in boxing was gone and that rowdies or groups of rowdies no longer could direct a decision by threats of what would happen in case it went contrary to their wishes. Bouts should be won in the ring, he said, and not in side rooms or back rooms.”

The mayor also stated that boxing had “never had an organization to go to the front for it” and that, if attacks were made in the future, the writers would “take up the cudgels for the game.”

“The dinner,” article concluded, “was interspersed with elaborate entertainment in which Broadway’s popular theatrical stars and widely known entertainers of the leading nightclubs of the city participated.”

One year later, the boxing writers returned to the Hotel Astor. This time, newly-crowned heavyweight champion Gene Tunney was the guest of honor. Tex Rickard was among the one thousand celebrants. And once again, Mayor Walker was there.

Times change. One hundred years ago, people got their news primarily through newspapers. Radio was just coming into its own as a force. Television was in the future. The National Football League was five years old. The National Basketball Association didn’t exist. Baseball and boxing were America’s two national sports.

Boxing is now a niche sport in America. The time when every major newspaper had a writer on staff who understood the sport and business of boxing and wrote regularly about it is long gone.

But the BWAA has survived. The awards that it bestows annually are still coveted. And with that in mind, I’d like to acknowledge some of boxing’s best from the past 100 years.

The BWAA began giving out annual awards in 1938 when it designated a “Fighter of the Year”. That was followed by the creation of awards for “Manager of the Year” (1967), “Excellence in Broadcast Journalism” (1982), “Trainer of the Year” (1989), and “Fight of the Year” (2002). Other awards have been created (including several for writers) but attract less attention.

So herewith, my choices for what I’ll call the BWAA “centennial awards”. Keep in mind that the timeline for consideration begins in 1925, which rules out fighters like Jack Johnson and the young Jack Dempsey.

The BWAA has never given out an award for “Promoter of the Year”. But a tip of the hat is in order to three men who took the sport to places it had never been to before.

Tex Rickard created the role of the modern promoter, made boxing respectable in the highest echelons of society, and fashioned the sport’s first $5m gates. Before the BWAA came into existence, Rickard promoted Jack Johnson v James Jeffries and Jack Dempsey’s fights against Jess Willard, George Carpentier and Luis Firpo. Later, he promoted Dempsey-Tunney I (which drew 120,757 fans to Sesquicentennial Stadium in 1926) and Tunney-Dempsey II (which brought 104,943 spectators to Soldier Field in 1927).

Rickard wasn’t a choir boy. In 1922, he was indicted on charges of abducting and sexually assaulting four underage girls. He was found “not guilty” after a trial relating to one of the girls and the other cases were then dropped. When he died in 1929, more than 10,000 mourners jammed Madison Square Garden for his funeral service and 10,000 more lined the streets outside.

Bob Arum began promoting fights in 1966. Since then, Top Rank (his promotional company) has promoted more than 2,000 fight cards and 700 world championship fights. Arum has been on the cutting edge of new technologies and was the first major player in boxing to understand and exploit the power of the Hispanic market in the United States.

Don King was larger than boxing; dominated the sweet science (and particularly the heavyweight division) during his glory years; and for decades was one of the most recognizable people on the planet. King had the genius to turn fights into events of sociological importance, as evidenced by his bringing Muhammad Ali v George Foreman to Zaire.

There have been other promoters worthy of note. Mike Jacobs controlled boxing at Madison Square Garden, Yankee Stadium and the Polo Grounds from the mid-1930s until 1946 when he suffered a stroke. Jacobs wasn’t a mobster but he made accommodations with the mob. Regional promoters like George Parnassus in Los Angeles and Herman Taylor in Philadelphia also left a mark. But Rickard, Arum, and King are “the big three”.

That said; Rickard took a sport that was illegal in most states, created events of extraordinary magnitude, and brought boxing to every level of American society. More than any other promoter, he left the sport better off than when he found it.

Managers

Jimmy Cannon once opined, “The fight manager wouldn’t fight to defend his mother. He has been a coward in all the important matters of his life. He is cranky and profane when he talks to the kids he manages, but he is servile when addressing the gangster whom he considers his benefactor. He has cheated many people but he describes himself as a legitimate guy at every opportunity.”

In 1967, rejecting that characterization, the BWAA began honoring a “manager of the year”.

A good manager can build a fighter from scratch and also take a successful fighter and make him better.

Jack Kearns was the quintessential manager of his time. Kearns was a crook. But he knew how to make money and build a fighter. He built Jack Dempsey, Mickey Walker and Joey Maxim, and later managed Archie Moore.

Al Weil (an equally unsavory character) managed Rocky Marciano, Marty Servo, Lou Ambers and Joey Archibald.

Other managers like Al Haymon (who’s also a de facto promoter) are worthy of note. But I’d highlight the job that Bill Cayton (with assistance from Jim Jacobs) did in managing Mike Tyson, Edwin Rosario and Wilfred Benitez and later (on his own) for Michael Grant and Tommy Morrison.

No one – and I mean, no one – did a better job of building a fighter from scratch than Cayton did with Tyson. And Cayton did the job remarkably well for his other fighters too. His personality sometimes grated on them. He wasn’t good at protecting his flank. Fighters left him. But they were usually less well off for leaving.

Broadcast journalism

Sam Taub was a journalist and radio broadcast commentator who covered boxing from the Roaring Twenties into the turbulent 1960s and would be forgotten today but for the award for “Excellence in Broadcast Journalism” that bears his name. The Sam Taub Award was first given out by the BWAA in 1982 when television was in full bloom. But the gospel of the sweet science was initially spread by radio.

Graham McNamee is widely regarded as the originator of play-by-play sportscasting and was behind the microphone for both Dempsey-Tunney fights in addition to numerous World Series and Rose Bowl games.

Joe Louis’s first-round knockout of Max Schmeling on 22 June 1938 was the high point of the marriage between boxing and radio. NBC carried the bout on 146 stations throughout the United States. Clem McCarthy called the blow-by-blow in what was arguably the most important sports broadcast of all time.

Gillette began sponsoring Friday night fights on radio in 1939. Don Dunphy’s first title fight behind the microphone was Joe Louis v Billy Conn in 1941. He called fights on the radio for Gillette for 19 years before segueing to ABC television in 1960.

Dunphy preferred to work solo on TV, saying that, when two or three people are involved in calling a fight, “they overtalk.” Asked by a young reporter why he sat silent for long stretches of time during a round rather than narrate the action, he replied, “Son, this is television. People can see what they’re doing.”

Howard Cosell rose to prominence in the 1960s as an ardent defender of Muhammad Ali and, for almost two decades, was synonymous with boxing on television. His presence at ringside made fights more important to viewers than might otherwise have been the case. Cosell has been dead for 30 years. But his cry of “Down goes Frazier! Down goes Frazier!” still reverberates.

Jim Lampley was HBO’s blow-by-blow commentator for 30 years and had everything necessary to be great. An understanding of the sport and business of boxing; the ability to summarize the action in terse sound bites as it unfolded (not two seconds later); and an electric voice that demanded attention.

Dunphy was the trailblazer. Cosell had the greatest impact. Lampley was the best. I’ll go with the best.

Trainers

George Gainford used to boast, “I’m the greatest trainer who ever lived. I trained Sugar Ray Robinson.” The response he often heard was, “George, you’ve had hundreds of fighters. Why weren’t they all as good as Sugar Ray?”

Most great trainers acknowledge that the fighter makes the trainer; not the other way around. But a good trainer helps. A lot.

Some legendary men have served as trainers over the past century. Ray Arcel, Jack Blackburn, Charlie Goldman, Cus D’Amato, George Benton and Emanuel Steward come to mind. But the honor is formally designated by the BWAA as “The Eddie Futch Trainer of the Year Award” for a reason.

“Mr Futch” (as he was known throughout boxing) helped mold countless world champions including Joe Frazier, Riddick Bowe, Michael Spinks, Ken Norton and Alexis Arguello. Freddie Roach has been honored with the Futch award a record seven times. But Roach would be the first to agree that Mr Futch (who was his mentor) was the master.

Fights

Let’s start with a clarification.

The rematch between Joe Louis and Max Schmeling was an event of monumental importance. But it wasn’t a great fight. The third encounter between Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier was as good as a fight can be. But it lacked the social and political significance of Ali-Frazier I (which was also a very good fight).

So which of the three fights just mentioned deserves recognition as the BWAA’s “centennial fight”?

When Joe Louis began his ring career, not a single black person played a prominent role in the American establishment. Moreover, as Arthur Ashe later noted, “Joe was the first black American of any discipline or endeavor to enjoy the overwhelming good feeling, sometimes bordering on idolatry, of all Americans regardless of color.”

All of Louis’s fights encompassed the issue of race. Louis-Schmeling II went beyond that. The bout was viewed as a test of decency and democracy versus Nazi doctrine and totalitarianism. Also, Ali-Frazier I was contested against the backdrop of a bitterly divided nation. But America was united in the hope that Louis would defeat Schmeling. It was the first time that many white Americans, particularly in the south, openly rooted for a black man to beat a white opponent.

Louis-Schmeling II was an annihilation rather than a competitive bout. But one-sided fights grow larger through the prism of history. And on that particular night, America wanted an annihilation.

So, yes; Ali-Frazier I captivated the world. But society was unchanged afterward. And if Ali had won that night (which he did in his next two fights against Frazier), the world wouldn’t have changed.

Louis-Schmeling II epitomizes the importance of boxing at its peak. That’s why it’s my BWAA “centennial fight”.

Fighters

That leaves the most important award of all: the BWAA Centennial Fighter.

Listed alphabetically, there are five entrants on my list: Muhammad Ali, Henry Armstrong, Sugar Ray Leonard, Joe Louis and Sugar Ray Robinson.

I’m looking here at skill rather than social significance. So right away, Joe Louis gives way to Ali.

Now we come to the three smaller fighters.

Boxing fans know that Henry Armstrong won multiple titles. But in recent decades, the concept of a “world champion” has been watered down. So let’s put what he did in perspective.

Armstrong fought 27 fights in 1937 and won all of them, 26 by knockout. He captured the featherweight crown that year by knocking out Petey Sarron. Then, over the next nine months, he added the welterweight championship with a lopsided decision over Barney Ross and annexed the lightweight title with a victory over Lew Ambers. He held three world championships simultaneously at a time when boxing had eight weight divisions with one champion in each division.

Sugar Ray Leonard was a complete fighter. He could box. He could punch. He had handspeed and heart and could take a punch. “And he was smart,” adds trainer Don Turner. “Bill Russell smart. Ray did whatever he had to do to win.”

Leonard won his first world championship in 1979 by knocking out Wilfred Benitez. Benitez was a true champion with a 38-0-1 record; not a mediocre alphabet-soup beltholder.

Then Leonard fought back-to-back fights against Roberto Duran, who had 72 victories in 73 bouts. Ray suffered the first loss of his career in their initial encounter. Defying the conventional wisdom that a fighter doesn’t come right back and beat the fighter who beat him, he fought an immediate rematch and forced Duran to say no más.

On 16 September 1981, Leonard fought Thomas Hearns. Hearns was undefeated, a ferocious puncher, 32-and-0 with 30 knockouts. Leonard-Hearns was a time-capsule fight. Ray dug deep, fought through adversity, showed every quality that a fighter needs to be great and stopped Hearns in the 14th round. That night, he entered the ranks of boxing immortals.

Six years later, Leonard cemented his legacy with a split-decision victory over Marvin Hagler. Prior to that bout, Hagler had won 11 consecutive middleweight championship fights and hadn’t lost in 11 years.

There’s a belief among knowledgeable boxing people that Sugar Ray Leonard is the best fighter to have plied his trade subsequent to Sugar Ray Robinson.

“Subsequent to Robinson.” That’s the key.

Robinson is the gold standard against which all fighters are judged.

“He had everything,” Eddie Futch said. “Boxing skills, punching power, a great chin, mental strength. There was nothing he couldn’t do. He knew almost everything there was to know about how to box. When Ray was in his prime, he owned the ring like no fighter before or since.”

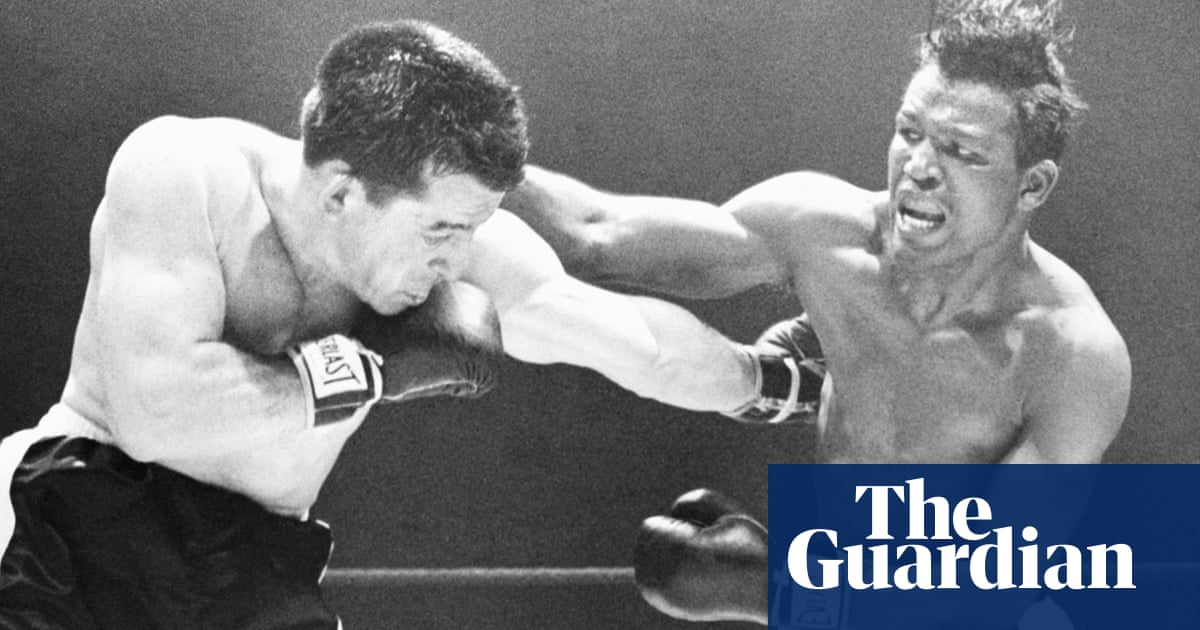

Robinson was a natural welterweight who knocked out middleweights with one punch. In his first 131 professional fights, he lost once. In 201 fights spanning 25 years (a career that began before Pearl Harbor and ended at the height of the war in Vietnam), he suffered a single “KO by”. That came when he challenged Joey Maxim for the light heavyweight championship and collapsed from heat prostration after controlling the fight for 13 rounds. Eighty-five years after his pro debut, Robinson is still thought of as the greatest fighter of all time.

As great as Muhammad Ali was, Sugar Ray Robinson is “The Centennial Fighter”.

-

The 100th annual BWAA Dinner featuring “Fighter of the Year” Oleksandr Usyk will be held on 30 April at the Edison Ballroom in Manhattan. Tickets for the event may be purchased through www.bwaa.org. or Gina Andriolo at [email protected].

-

Thomas Hauser’s email address is [email protected]. His most recent book – MY MOTHER and me – is a personal memoir available at Amazon.com. In 2004, the Boxing Writers Association of America honored Hauser with the Nat Fleischer Award for career excellence in boxing journalism. In 2019, Hauser was selected for boxing’s highest honor – induction into the International Boxing Hall of Fame.