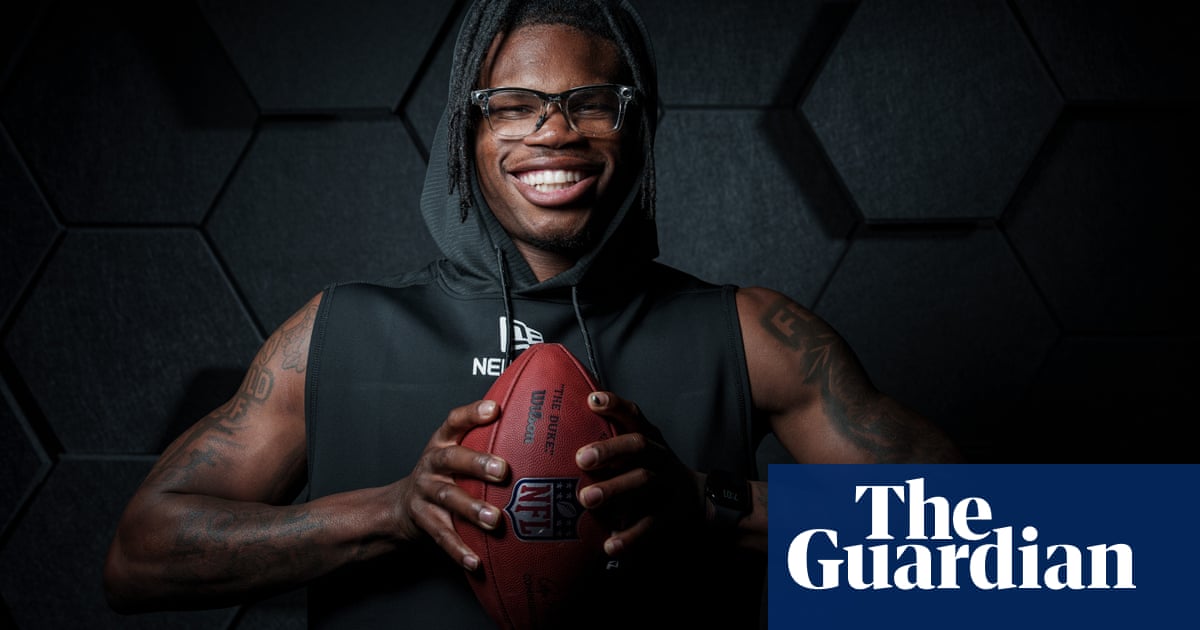

Every once in a while, a player comes along who breaks our understanding of a sport. Basketball has Victor Wembanyama. Baseball has Shohei Ohtani. For professional football, enter Travis Hunter.

There are good prospects, there are great prospects, and then there is whatever Hunter is. The Heisman Trophy winner and soon-to-be top-five draft pick is looking to do the improbable: play both sides of the ball in the NFL, offense and defense, full-time.

Some college prospects major in one position and minor in another. Some switch positions once they arrive in the league. Hunter is the first elite college player this century to line up on both sides of the field for entire games, dominating at two positions. In his final season at Colorado, Hunter played 713 snaps on offense and 748 on defense on his way to winning the Heisman Trophy, switching between cornerback and receiver.

The draft has never seen anything like it, a player who could be the keystone on offense and defense.

With Hunter, the talent is overwhelming and obvious. As both a corner and receiver, he moves differently. He thinks differently. Somehow, the league has a draft class where the same person is the best cornerback and receiver.

Now, NFL teams have to figure out what in the hell they are going to do with the supernova talent. Do they limit him one role or allow him to try to play both? The downside of not letting him try: “It’s never playing football again,” Hunter told Garrett Podell of CBS Sports. “Because I’ve been doing it my whole life, and I love being on the football field. I feel like I could dominate on each side of the ball, so I really enjoy doing it.”

That’s an idle threat – Hunter won’t walk away from millions of dollars because a team won’t let him play corner. But it’s indicative of his mindset. He wants to be the crux of a team’s offense and defense.

Plenty of people believe that is impossible. “There’s absolutely no way he can do them both full-time,” one executive told Go Long. “They’ll just wear him out. Each team will look at him differently as far as what they want to do with him.”

Hunter’s insistence on playing both ways will be a paradigm shift for a sport built on specialists. What meeting room will he sit in? Who will be his position coach? What will his contract look like? Will splitting time cap his talent at one position? How do you manage his reps? If he plays both ways, Hunter will be taking on twice the injury risk, perhaps even more so with the accumulated fatigue.

“What he would attempt to do has not really been done in our league,” Andrew Berry, the general of the Cleveland Browns, who hold the No 2 overall pick in the draft, said last week. “But, we wouldn’t necessarily put a cap or a governor in terms of what he could do. We would want to be smart in terms of how we started him out.”

For his part, Hunter has cited NFL games being slower than in college, with roughly 35 seconds between snaps, and the minimal contact he will absorb at each position as the reasons why he can continue to manage the workload.

It’s a small crop of players who have ever had the technical, intellectual or athletic qualities to consider lining up two ways. Deion Sanders, the Hall of Fame cornerback who coached Hunter in college, was a situational wide receiver during the prime of his career (as well as playing Major League Baseball). Charles Woodson, another Hall of Fame defensive back, returned kicks and caught a few passes at Michigan. In the NFL, he was an all-world defensive back who caught only two passes on offense. Champ Bailey, who is commonly compared to Hunter, caught 59 catches in college and teased that he would play both ways in the pros. He finished with just four receptions during his 15-year, Hall of Fame career as a lockdown corner.

On the offensive side, the history is more limited. New England wide receiver Julian Edelman was used as an emergency cornerback, but only in rare circumstances. Small, goalline packages are where players typically dabble with switching sides of the ball, usually to add some extra beef on to the field. But the grind of an NFL season makes it tough for teams to chuck a player on the field for an entire game. “You’re always worried about the length of the season in the NFL,” Giants GM Joe Schoen said at this year’s Combine. “If he gets hurt doing something that he’s not doing full-time, you’re going to kick yourself.”

Teams have discussed a set package of plays for Hunter. But building an individual collection of plays for a single player is tricky. It steals away precious practice reps, and can turn an offense (or defense) predictable, a cardinal sin for most coaches. Hey, here comes the Travis package. We know what they’re trying to run!

after newsletter promotion

NFL players are masters of their chosen craft. Covering professional receivers is a full-time gig. The top cornerbacks pile hours into film study, allowing them to leap routes and concepts before they develop. Professional offenses are built on rhythm, timing and the chemistry between the quarterback and his receivers. It is the accumulation of thousands of practice hours. With the current Collective Bargaining Agreement, there are strict parameters on how often and for how long teams can practice. It will be tough for Hunter to get enough time to perfect his craft on one side of the ball while cameoing elsewhere.

There is a question of value, too. If Hunter can only play one role full-time while having a limited package of plays elsewhere, in which spot will a team extract the most juice?

As a cornerback, Hunter has rare vision. There is an artistry that allows him to undercut routes to make plays. And he is always – always – around the ball. And when he’s not, it’s because the opposing offense has done whatever it can to remove him from the picture, in case he peels off his intended assignment to hunt for the ball. He is not the kind of corner who will lock down a side of the field for an entire game; he is out there to force turnovers. With that profile, it is difficult for a team to ensure that the most gifted player on their squad will touch the ball. On offense, there is more certainty: teams can manufacture touches or design plays with the sole purpose of getting the ball in Hunter’s hands.

Yet as a receiver, Hunter is a little sloppier, possibly due to the sheer exhaustion of totting up 100-plus snaps a game. He is less refined on offense than on defense, but just as dynamic. There is some Justin Jefferson to Hunter’s receiver game, skipping across the grass like he’s moving in fast-forward. He bobs and weaves through coverage, subtly shifting gears to force defenders off balance before driving to his destination. And he grabs everything, happy to leap up for highlight reel grabs or absorb heavy shots in the middle of the field to keep the chains moving.

The calculation runs something like this: As a receiver, he may be one of the 10 best in the league; as a corner, he may be the most impactful. But for a team to sacrifice the offensive production for the defensive payoff, Hunter would probably have to post double-digit turnovers a season, and turnovers are a volatile figure that no player can guarantee.

What Hunter wants is different from how a team can maximize him. If Hunter hits his ceiling as a receiver, he will be among Jefferson, Ja’Marr Chase and AJ Brown at the top of the charts. Yet even if he is, say, the eighth-best wideout in football, that is more valuable than a top-tier cornerback in the offense-first, pass-happy era. As a cornerback, Hunter’s ceiling is different. There, we are talking not just about on-field production, but changing the fabric of the position. Now we are in gold jacket territory. You’re talking about a generation growing up wanting to play a position because they want to be like Travis, a dynamic, game-tilting cornerback who fuels paranoia in the league’s quarterback. One may be more valuable to Hunter; the other may be more valuable to a team.

“A lot of teams don’t know what to do with me,” Hunter told NBC Sports. “They’ve seen me do it at the college level. Nobody actually thought I’d be able to do it at the college level, so everybody is amazed that I’ve done it for this long and I’ve done it at a high level.”

Where Hunter plays will most likely come down to one of two teams: the Browns or the Giants, who pick second and third in the draft. Will they let him be the football answer to Ohtani? It would feel like a crime against football not to let him try.